IQOS. Monitoring their effects and developing appropriate legislation is crucial for protecting public health and informing consumers.

It appears that IQOS and heated tobacco products represent a new effort to perpetuate smoking habits and maintain the profits of the tobacco industry, as has been the case in previous years with other tactics such as light cigarettes, filters, etc.

Heated Tobacco Products

Development & Impact

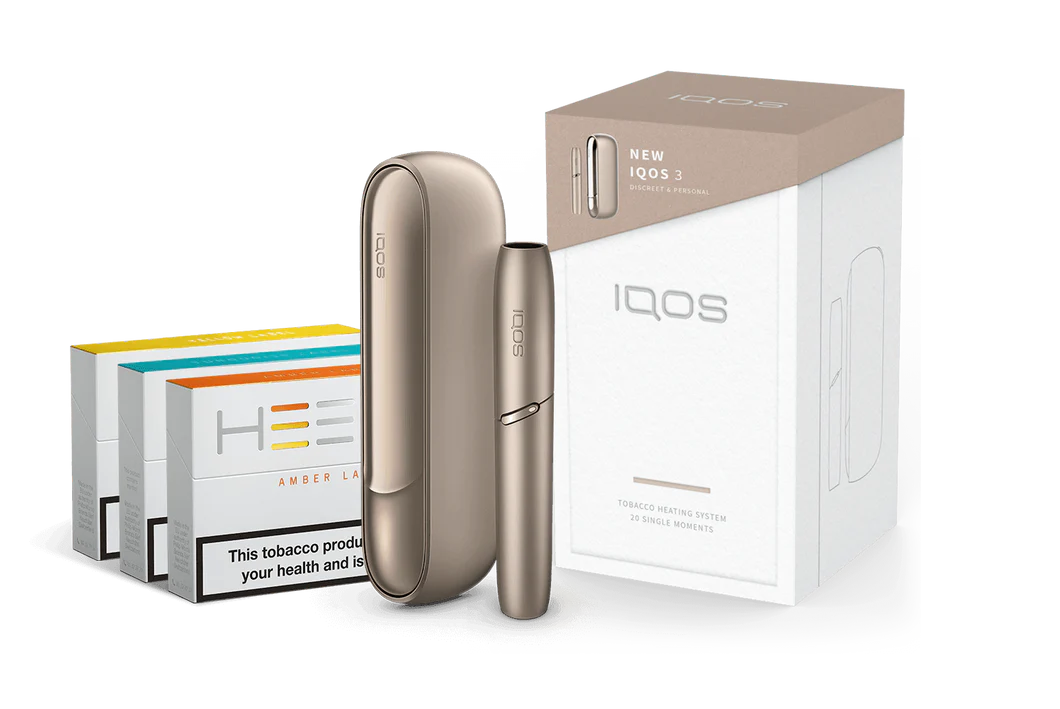

Heated tobacco products are a new nicotine delivery system presented by the tobacco industry as “heat-not-burn” products.

These products consist of a base-receptor that heats a tobacco stick. The tobacco industry actively promotes these products, such as IQOS, BLOw, and RIVO.

The research of the tobacco industry claims a reduction of damages by 90-95%.

According to a press release from the tobacco industry, the primary ingredient in heated tobacco products is water, while the main ingredient in conventional cigarettes is tar.

In this way, the tobacco industry claims a 90-95% reduction in harmful substances and toxicity of these products.

Digging deeper into tobacco industry research on heated tobacco products:

Tobacco companies do not inform the public that some harmful ingredients were found in increased concentrations in their studies, such as suspended particles, tar, acetaldehyde (carcinogenic), acrylamide (potential carcinogen), and a metabolite of acrolein that is toxic and irritant.

Some studies found significantly increased concentrations of formaldehyde (a potential carcinogen) in heated tobacco products compared to conventional cigarettes.

Independent studies have shown a significantly increased risk compared to what the tobacco industry claims.

Historically, there is strong evidence that studies conducted or funded by the tobacco industry cannot be reliable. Former employees or insiders of tobacco companies have described serious irregularities in clinical experiments on heated tobacco products conducted by them.

Independent research has shown that acrolein (a toxic and irritant substance) is reduced by only 18%, formaldehyde (potential carcinogen) by 26%, benzaldehyde (potential carcinogen) by 50%, and levels of TSNAs (carcinogens) are detected at 1/5 compared to conventional cigarettes.

Additionally, the potential carcinogenic substance acenaphthene is found at least three times higher levels compared to conventional cigarettes, and levels of nicotine and tar have been found to be nearly the same as those in conventional cigarettes.

An experimental study on animals found that exposure to iQOS led to a 60% reduction in blood vessel function, a percentage comparable to that caused by conventional cigarettes.

Finally, a study found that iQOS users may need to smoke at such a fast rate that it could lead to increased intake of carbonyls (potential carcinogens) and nicotine, thus causing high levels of nicotine addiction.

What does the European Respiratory Society consist of?

Even if heated tobacco products may potentially be less harmful for smokers, they still remain highly harmful and addictive. There is an increased risk that smokers will ‘transition’ to these products instead of quitting smoking altogether.

The European Respiratory Society cannot endorse any product that is harmful to the lungs and human health.

Why does the ERS make this recommendation?

ERS (European Respiratory Society) and other medical organizations have already made several recommendations regarding the use of e-cigarettes and other tobacco products based on current scientific research and health data.

Specifically, the ERS and other medical bodies express concern about the use of e-cigarettes due to the high health risks it may pose to users.

Heated tobacco products:

- Are harmful and addictive.

- Undermine smokers’ desire to quit smoking.

- Undermine the desire of former smokers to remain smoke-free.

- Are a temptation for non-smokers and young people.

- Pose a risk of normalizing harmful smoking habits.

- Pose a risk of simultaneous use with conventional cigarettes.

It is tempting to suggest to smokers to switch to heated tobacco products without considering all the consequences. Our experience, for example with filtered cigarettes and lights (“light” cigarettes), has shown that the “safer products” undermine smokers’ desire to quit and have not improved smokers’ health.

Below are references from the tobacco industry regarding “safer products”: “Smokers who want to quit smoking should be discouraged or at least maintained in the market in the long term.

It should also be remembered that 2-3 out of 4 smokers want to quit smoking, and almost all smokers regret starting smoking. Additionally, many smokers want to quit smoking because they want to regain control of their lives and overcome nicotine addiction – this will not happen if they switch to heated tobacco products.

Furthermore, we have not proven that heated tobacco products are effective as a cessation aid.

Conclusions

Heated tobacco products, conventional cigarette smoking, and the use of tobacco for oral or nasal use are all addictive and carcinogenic to humans.

We should not allow discussion about new tobacco products to distract us from our fundamental obligation: to promote regulatory measures that we know are effective in reducing smoking and to support those who want to quit.

Bibliography

- Gilcrist M. Heat-not-burn products. Scientific Assessment of Risk Reduction. In: International PM, ed. Global Tobacco and Nicotine Forum 2015 Annual Meeting Sept 17, 2015

- Szostak J, Boue S, Talikka M, et al. Aerosol from Tobacco Heating System 2.2 has reduced impact on mouse heart gene expression compared with cigarette smoke. Food and chemical toxicology : an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association 2017;101:157-67. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2017.01.013 [published Online First: 2017/01/24]

- Tricker AR, Stewart AJ, Leroy CM, et al. Reduced exposure evaluation of an Electrically Heated Cigarette Smoking System. Part 3: Eight-day randomized clinical trial in the UK. RegulToxicolPharmacol 2012;64(2 Suppl):S35-S44.

- Tricker AR, Jang IJ, Martin LC, et al. Reduced exposure evaluation of an Electrically Heated Cigarette Smoking System. Part 4: Eight-day randomized clinical trial in Korea. RegulToxicolPharmacol 2012;64(2 Suppl):S45-S53.

- Tricker AR, Kanada S, Takada K, et al. Reduced exposure evaluation of an Electrically Heated Cigarette Smoking System. Part 5: 8-Day randomized clinical trial in Japan. RegulToxicolPharmacol 2012;64(2 Suppl):S54-S63.

- Tricker AR, Kanada S, Takada K, et al. Reduced exposure evaluation of an Electrically Heated Cigarette Smoking System. Part 6: 6-Day randomized clinical trial of a menthol cigarette in Japan. RegulToxicolPharmacol 2012;64(2 Suppl):S64-S73.

- Urban HJ, Tricker AR, Leyden DE, et al. Reduced exposure evaluation of an Electrically Heated Cigarette Smoking System. Part 8: Nicotine bridging–estimating smoke constituent exposure by their relationships to both nicotine levels in mainstream cigarette smoke and in smokers. RegulToxicolPharmacol 2012;64(2 Suppl):S85-S97.

- Stabbert R, Voncken P, Rustemeier K, et al. Toxicological evaluation of an electrically heated cigarette. Part 2: Chemical composition of mainstream smoke. JApplToxicol 2003;23(5):329-39.

- Proctor RN. Golden Holocaust. Origins of the Cigarette Catastrophe and the Case for Abolition. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press 2011.

- Barnes DE, Hanauer P, Slade J, et al. Environmental tobacco smoke. The Brown and Williamson documents. JAMA 1995;274(3):248-53.

- Hong MK, Bero LA. How the tobacco industry responded to an influential study of the health effects of secondhand smoke. BMJ 2002;325(7377):1413-16.

- Barnes DE, Bero LA. Industry-funded research and conflict of interest: an analysis of research sponsored by the tobacco industry through the Center for Indoor Air Research. JHealth PolitPolicy Law 1996;21(3):515-42.

- Barnes DE, Bero LA. Why review articles on the health effects of passive smoking reach different conclusions. JAMA 1998;279(19):1566-70.

- Reuters Investigates. The Philip Morris files. 2017.

- Auer R, Concha-Lozano N, Jacot-Sadowski I, et al. Heat-Not-Burn Tobacco Cigarettes: Smoke by Any Other Name. JAMA internal medicine 2017;177(7):1050-52. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1419 [published Online First: 2017/05/23]

- Bekki K, Inaba Y, Uchiyama S, et al. Comparison of Chemicals in Mainstream Smoke in Heat-not-burn Tobacco and Combustion Cigarettes. Journal of UOEH 2017;39(3):201-07. doi: 10.7888/juoeh.39.201 [published Online First: 2017/09/15]

- Li X, Luo Y, Jiang X, et al. Chemical Analysis and Simulated Pyrolysis of Tobacco Heating System 2.2 Compared to Conventional Cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res 2018 doi: 10.1093/ntr/nty005 [published Online First: 2018/01/11]

- Nabavizadeh P, Liu J, Ibrahim S, et al. Poster presentation: Inhalation of Heat-Not-Burn Tobacco Aerosol Impairs Vascular Endothelial Function: Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education, 2017.

- Davis B, Williams M, Talbot P. iQOS: evidence of pyrolysis and release of a toxicant from plastic. Tob Control 2018 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-054104 [published Online First: 2018/03/15]

- Harris JE, Thun MJ, Mondul AM, et al. Cigarette tar yields in relation to mortality from lung cancer in the cancer prevention study II prospective cohort, 1982-8. Bmj 2004;328(7431):72. doi: 10.1136/bmj.37936.585382.44 [published Online First: 2004/01/13]

- Cunningham R. Smoke and mirrors : the Canadian tobacco war. Note on: Creative Research group, Project Viking, Volume 11: An Attitudinal Model of Smoking, 1986, February- March, prepared for Imperial Tobacco Limited (Canada). International Development Reasearch Center1996.

- Rosendahl Jensen H, Davidsen M, Ekholm M, et al. Danskernes Sundhed – Den Nationale Sundhedsprofil 2017. (National Health Survey 2017). www.sst.dk. Sundhedsstyrelsen, Islands Brygge 67, 2300 København S: Danish National Board of Health, 2018.

- Sansone N, Fong GT, Lee WB, et al. Comparing the Experience of Regret and Its Predictors Among Smokers in Four Asian Countries: Findings From the ITC Surveys in Thailand, South Korea, Malaysia, and China. NicotineTobRes 2013;15(10):1663-72.

- Fong GT, Hammond D, Laux FL, et al. The near-universal experience of regret among smokers in four countries: findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Survey. NicotineTobRes 2004;6 Suppl 3:S341-S51.

- McCaul KD, Hockemeyer JR, Johnson RJ, et al. Motivation to quit using cigarettes: a review. Addict Behav 2006;31(1):42-56. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.004 [published Online First: 2005/05/27]

- Ahluwalia JS, McNagny SE, Clark WS. Smoking cessation among inner-city African Americans using the nicotine transdermal patch [see comments]. J GenIntern Med 1998;13(1):1-8.

- Edwards R, Tu D, Newcombe R, et al. Achieving the tobacco endgame: evidence on the hardening hypothesis from repeated cross-sectional studies in New Zealand 2008-2014. Tob Control 2017;26(4):399-405. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052860 [published Online First: 2016/07/07]

- Eriksen M, Mackay J, Ross H. The Tobacco Atlas: American Cancer Society. 250 Williams Street. Atlanta, Georgia, 30303 USA 2012.

- Bommel‚ J, Nagelhout GE, Kleinjan M, et al. Prevalence of hardcore smoking in the Netherlands between 2001 and 2012: a test of the hardening hypothesis. BMCPublic Health 2016;16

- Reid JL, Rynard VL, Czoli CD, et al. Who is using e-cigarettes in Canada? Nationally representative data on the prevalence of e-cigarette use among Canadians. PrevMed 2015;81:180-83.

- Christensen T, Welsh E, Faseru B. Profile of e-cigarette use and its relationship with cigarette quit attempts and abstinence in Kansas adults. Prev Med 2014;69:90-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.09.005 [published Online First: 2014/09/18]

- Lund I, Scheffels J. Adolescent tobacco use practices and user profiles in a mature Swedish moist snuff (snus) market: Results from a school-based cross-sectional study. Scand J Public Health 2016 doi: 10.1177/1403494816656093 [published Online First: 2016/06/25]

- Wells Fargo: Probability Of PM/MO Combo Now Higher – iQOS Remains A Key Catalyst & Is Driving Transformative Growth. Wells Fargo Securities, LLC, 18. 12. 2016.

- Answer given by Mr Andriukaitis on behalf of the Commission, Parliamentary questions, available at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getAllAnswers.do?reference=P-2016-009191&language=ES#def1 9 January 2017

- Statement on the toxicological evaluation of novel heatnot-burn tobacco products, COMMITTEES ON TOXICITY, CARCINOGENICITY AND MUTAGENICITY OF CHEMICALS IN FOOD, CONSUMER PRODUCTS AND THE ENVIRONMENT (COT, COC and COM), 11 December 2017.

- LaVito A. In high-stakes votes, FDA advisors say evidence doesn’t back Philip Morris’ claims. CNBC Health Care 25.01.2018.

- WHO. International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. 2014.

- IARC. IARC strenghthens its findings on several carcinogenic personal habits and household exposure, World Health Organisation, International Agency for Research on Cancer, 02 November 2009.